Russian Turkestan -- modernization

Settled elites dealt with Russians mostly in commerce, which had deep, long-term effects on individual and communal identities. The Russians reduced Bukhara and Khiva to protectorate status, which left their political structures intact but with severely weakened legitimacy in the eyes of their subjects. Behind the facade of traditional rule, Russian power became increasingly visible through the railroad—built in 1885—that linked Ashkhabad with Tashkent via Bukhara. In Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent and several towns in the Ferghana Valley Russian “new” cities developed alongside the old Central Asian cities. The new Russian settlements were inhabited by administrators, doctors, teachers, and entire families, who required very different living conditions than did soldiers in barracks. Accordingly, the new Russian cities featured wide boulevards, parks, and churches. There was apparently no permanent European settlement in Khiva, aside from isolationist German Mennonite and Cossack communities.

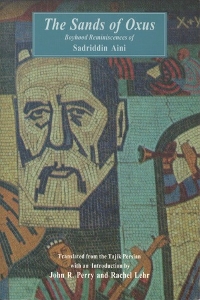

Sadriddin Aini (1878–1954)

Aini was a Jadidist, but also a prolific writer of poetry and scholarly work. His memoir of growing up in a village outside of Bukhara is a wonderful, lively description of everyday life in this period and would be excellent for classroom use. The Sands of Oxus: Boyhood Reminiscences of Sadriddin Aini (Cosa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1998), translated and annotated by John R. Perry and Rachel Lehr.

Merchants and commerce

Turkestani merchants had traded with Russia for centuries, but exchanging fancy dyed textiles for samovars was very different from having Russians (and their Tatar interpreters) actually move in. The Russians restructured much of the Turkestani economy, turning it into a producer of raw textile materials for the Russian market. As in British India, natives were limited to growing and processing cotton and silk, which was then shipped to Russia for finishing. The Turkestanis who ran cotton ginning mills, who served as high-level mediators between the emir and Russian bureaucrats, or who governed on behalf of the Russian administration found themselves becoming a new kind of community— a modern community. This community of modernized Turkestanis was marked by several characteristics:

•modern Turkestanis were embedded within an international web of political and commercial connections that extended from home to St. Petersburg and the rest of Christian Europe, more than to Persia, India, or the Ottoman Empire;

•their political allegiance shifted from local tribal hierarchies to Russian government officials;

•they did not come from the traditional warrior elites, but from the more flexible merchant and clerical groups;

•they spoke, dressed, and behaved more like Russians than Turkestanis, yet remained distinct from Russians;

•they were more interested in prospering in this new world than in preserving the old.

Education

Turkestani elites came to value Russian education as beneficial for their children’s futures. This process took several decades. Russians established the first Russian-native schools in Turkestan in the 1870s. These schools taught arithmetic, geography, and basic literacy in Türki and Russian, alongside the traditional Islamic curriculum. By 1909 there were 98 of these schools and approximately 450 students in the province, compared with thousands of traditional Muslim elementary schools (called maktabs). A handful of Turkestani boys were sent to study in St. Petersburg or Moscow. In Bukhara, even the Islamic seminary (madrasa) faculty allowed a Russian doctor to lecture on medical science [Keller, 2001, pp. 18–20; Khalid, p. 84]. While the number of Russian-educated Turkestanis was always very small, their positions as intermediaries between the state and the people gave them disproportionate power. The educational process itself had some surprisingly wide effects. For example, in order to write textbooks for Turkestani children, educators had to codify a standard Turkic language out of a number of regional dialects. This newly-standardized language would become the basis for modern Uzbek in the twentieth century.

The Russians brought Tatar interpreters with them, and many of these Tatars stayed even after a cohort of Turkestanis had mastered Russian (this can be roughly dated to the 1880s). The Tatars, after more than 300 years of Russian rule, were much more comfortably westernized than were Turkestanis. Tatars preferred to live in Russian neighborhoods and send their children to Russian schools (the Russians maintained a separate all-Russian school system for their own children). Tatar men could serve as military officers, and Tatar women did not cover their faces in public. Tatars viewed themselves as culturally superior to Turkestanis, and worked hard to enlighten their eastern cousins by teaching in Russian-native schools or serving as doctors and midwives. Not only were they an important vehicle for modernizing the new Turkestani elite, they also provided a new model of Muslim behavior that Turkestanis could embrace, reject, or adapt, and in doing so define their own developing identities. Historian Marianne Kamp provides an excellent example of the tensions and excitement between Tatars and Turkestanis when she discusses the passionate debates over women’s status in the two communities [Kamp, pp. 35–40].

The most consciously modern group of Turkestanis are known to us as the Jadids. The Jadid movement was another Tatar import, founded in the 1880s by Ismail Bey Gaspirali in the Crimea. The first Jadid school opened in Samarkand in 1893. Within ten years Jadid schools operated not only in most larger towns, but also spread east into the Kyrygyz steppelands and Xinjiang as well. Two points of interest: A) the men who made up this movement were themselves a bridge population between traditional and modern Turkestani identity structures. Many Jadid reformers were educated in madrasas, so they were at home with traditional Islamic practices. They did not want to secularize their society, but to use Western methods of literacy training and scientific reasoning to improve and strengthen Turkestani cultures. B) The Jadids were a minority within the minority of modernized Turkestanis. Their educational methods made Jadid schools attractive to the rising merchant class, but the Jadid interest in independence caused the authorities—on whom those same merchants depended—to treat them with great suspicion. The Jadid movement remained very small before 1917, but then they found new patrons in the Bolsheviks, who pursued a much more radical form of modernization. The Bolsheviks would find the Jadids a useful bridge population for their own political program, at least for the first ten years after the revolution.

Ordinary people

What about the vast majority of Turkestanis, who never interacted with Russians and who did not have higher educations in any language? We know very little. Farmers were pushed into growing cotton as a cash crop, a process that gradually eroded their dependence on tribal or village leaders and instead put them at the mercy of Russian and international markets. Leaders who could no longer provide goods or fighting prestige then lost their status, making it less important to remember who their descendants were. A military statistical survey of the region published in 1903 said that Uzbek tribes were identifying more with the towns where they lived than with the line of their ancestors [Geiss, p. 231]. This suggests that they had made a major break from the old ways of establishing identity.

The new silk- and cotton-processing factories needed local labor, and so a working population (too small to be called a “working class”) developed. The 1897 Imperial Russian census reported that 10.7% of women in the Ferghana region were employed, mostly in textile production. By 1914 Russian surveyors counted 20,925 industrial workers in Turkestan, out of a total population of 6.5 million [Allworth, pp. 93, 320]. Some of these workers gained access to greater education—in the town of Andijan an Uzbek factory owner sponsored a Jadid school for the children of his workers, although few other owners were so generous [Keller, 2001, p. 23].

The Russian Empire was disrupted by increasing violence during the last decades of its existence, from the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 to the 1905 Revolution, the Lena Goldfield Massacre of 1912, World War I, and finally the revolutions of 1917. Turkestanis did not participate in these events until 1916, when anti-draft riots turned into large-scale attacks on Imperial agents and on Slavic settlers in the Kyrgyz steppelands. The catastrophic fighting of 1916–1917, in which many more Turkestanis than Russians died, cannot be characterized as a nationalist uprising, but as violence driven by anger at economic and political oppression.

Summary of the imperial period

Conquest by the Chinese and Russian empires brought enormous changes to Central Asian societies. Politically, Central Asian khanates lost their independence and the Khanate of Kokand was destroyed. For ordinary Central Asians, especially those who fell under Russian governance, these changes turned out to mean more than paying old taxes to new rulers. The steppe lands where nomads grazed their herds were divided under administrative rules set in St. Petersburg, and then settled by increasing numbers of Slavic farmers. Tribal leaders and Islamic judges had their power redefined and curtailed by Russian bureaucrats, while the emir of Bukhara and the khan of Khiva could only do what the Russians allowed them to. Meanwhile the residents of Tashkent found their city growing rapidly in importance as the Russian administrative center. The loss of political independence was less of a shock for Muslims of the Xinjiang “new frontier,” because they had not governed themselves for a century before the Qing arrived.

All Central Asians found themselves being drawn into the modern global economy, which meant new mercantile and industrial wealth for a few and impoverishment for many. Economic changes in turn drove social changes, as new elites emerged and the old structures of genealogy and tribal custom lost their importance. By 1917, however, it was still not accurate to refer to the “nations of Central Asia” as one would have referred to the “nations of Europe.” Individual and communal identities were changing rapidly, but it took the wars and revolutions of the twentieth century to thoroughly transform the bases of identity structures.