Introduction: Like a Civil War

Introduction: Like a Civil War

"We have not yet achieved justice. We have not yet created a union which is, in the deepest sense, a community. We have not yet resolved our deep dubieties or self-deceptions. In other words, we are sadly human, and in our contemplation of the Civil War we see a dramatization of our humanity; one appeal of the War is that it holds in suspension, beyond all schematic readings and claims to total interpretation, so many of the issues and tragic ironies -- somehow essential yet incommensurable -- which we yet live." -- Robert Penn Warren, The Legacy of the Civil War, 1961.

As the 1950s drew to a close, the organizers of the official centennial observances for the Civil War scheduled to begin in the spring of 1961 and to run through the spring of 1965, were determined not to allow their project to become bogged down in any outmoded animosities. Among other considerations, much was at stake in a successful centennial for the tourism, publishing, and souvenir industries; as Karl S. Betts of the federal Civil War Centennial Commission, predicted expansively on the eve of the celebration, "It will be a shot in the arm for the whole American economy." Naturally, the shot-in-the-arm would work better if other kinds of shots, those dispensed from musketry and artillery that caused the death and dismemberment of hundreds of thousands of Americans between 1861 and 1865, were not excessively dwelt upon. The Centennial Commission preferred to present the Civil War as, in essence, a kind of colorful and good-natured regional athletic rivalry between two groups of freedom-loving white Americans. Thus, the Commission's brochure "Facts About the Civil War" described the respective military forces of the Union and the Confederacy in 1861 as "The Starting Line-ups."

Nor did it seem necessary to remind Americans in the 1960s of the messy political issues that had divided their ancestors into warring camps a century earlier. "Facts About the Civil War" included neither the word "Negro" nor the word "slavery." When a journalist inquired in 1959 if any special observances were planned for the anniversary of Lincoln's emancipation proclamation three years hence, Centennial Commission director Betts hastened to respond, "We're not emphasizing Emancipation." There was, he insisted "a bigger theme" involved in the four year celebration than the parochial interests of this or that group, and that was "the beginning of a new America" ushered in by the Civil War. While memories of emancipation -- the forced confiscation by the federal government of southern property in the form of four million freed slaves -- were divisive, other memories of the era, properly selected and packaged, could help bring Americans together in a sense of common cause and identity. As Betts explained: The story of the devotion and loyalty of Southern Negroes is one of the outstanding things of the Civil War. A lot of fine Negro people loved life as it was in the old South. There's a wonderful story there -- a story of great devotion that is inspiring to all people, white, black or yellow.

But contemporary history sometimes has an inconvenient way of intruding upon historical memory. As things turned out, at the very first of the scheduled observances, the commemoration of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, the well-laid plans of the centennial's publicists began to go awry. The Centennial Commission had called a national assembly of delegates from participating state civil war centennial commissions to meet in Charleston. When a black delegate from New Jersey complained that she was denied a room at the headquarters hotel because of South Carolina's segregationist laws, four northern states announced they would boycott the Charleston affair. In the interests of restoring harmony, newly-inaugurated President John F. Kennedy suggested that the state commissions' business meetings be shifted to the non-segregated precincts of the Charleston Naval Yard. But that, in turn, provoked the South Carolina Centennial Commission to secede from the federal commission. In the end, two separate observances were held, an integrated one on federal property, and a segregated one in downtown Charleston. The centennial observances, Newsweek magazine commented, "seemed to be headed into as much shellfire as was hurled in the bombardment of Fort Sumter...."

In the dozen or so years that followed, Americans of all regions and political persuasions were to invoke imagery of the Civil War -- to illustrate what divided rather than united the nation. "Today I have stood, where once Jefferson Davis stood, and took an oath to my people," Alabama governor George Wallace declared from the steps of the state house in Montgomery in his inaugural address in January 1963. From "this Cradle of the Confederacy....I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny...and I say....segregation now...segregation tomorrow...segregation forever!" Six months later, in response to civil rights demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama, President Kennedy declared in a nationally televised address to the nation: "One hundred years of delay have passed since President LIncoln freed the slaves...[T]his Nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free." Two years later, in May 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. stood on the same statehouse steps in Montgomery where Governor Wallace had thrown down the gauntlet of segregation. There, before an audience of twenty five thousand supporters of voting rights, King ended his speech with the exaltedly defiant words of the "Battle Hymn of the Republic": "Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord, trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored. He has loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword. His truth is marching on....

Glory, glory hallelujah!

Glory, glory hallelujah!

Glory, glory hallelujah!"

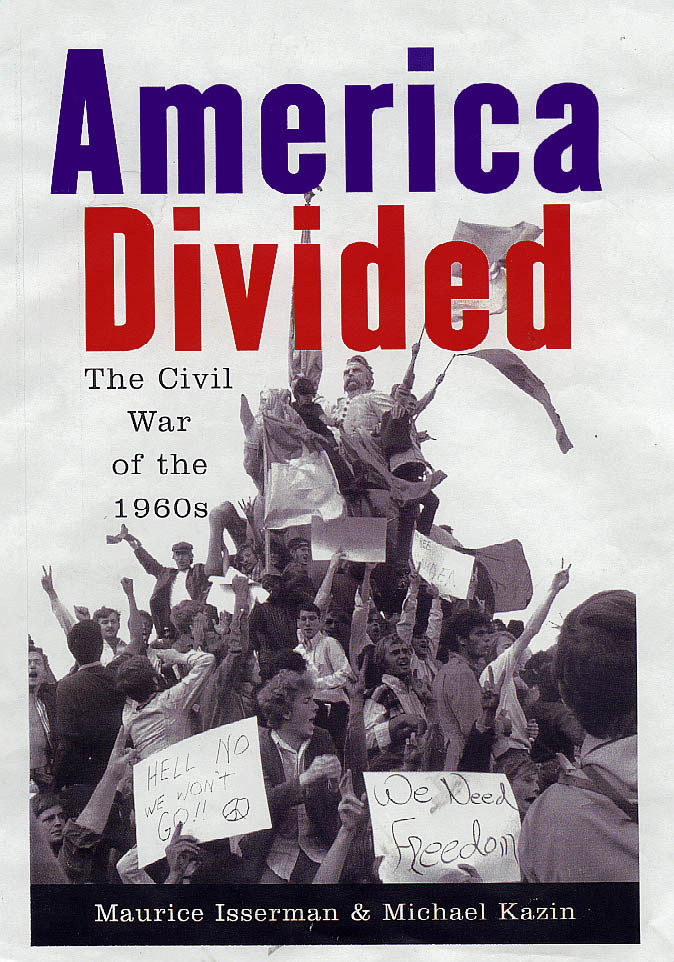

To its northern and southern supporters, the civil rights movement was a "Second Civil War," or a "Second Reconstruction." To its southern opponents, it was a second "war of northern aggression." Civil rights demonstrators in the South carried the Stars and Stripes on their marches; counter-demonstrators waved the Confederate Stars and Bars. The resurrection of the battle cries of 1861-65 was not restricted to those who fought on one or another side of the civil rights struggle. In the course of the 1960s, many Americans came to regard groups of fellowcountrymen as enemies with whom they were engaged in a struggle for the nation's very soul. Whites versus blacks, liberals versus conservatives (as well as liberals versus radicals), young versus old, men versus women, hawks versus doves, rich versus poor, taxpayers versus welfare recipients, the religious versus the secular, the hip versus the straight, the gay versus the straight -- everywhere one looked, new battalions took to the field, in a spirit ranging from that of redemptive sacrifice to vengeful defiance. When liberal delegates to the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago lost an impassioned floor debate over a proposed anti-war plank in the party platform, they left their seats to march around the convention hall singing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic." Out in the streets meanwhile, watching the battle between Chicago police and young anti-war demonstrators, the middle-aged novelist Norman Mailer admired the emergence of "a generation with an appetite for the heroic..." It pleased him to think that "if it came to civil war, there was a side he could join." New York Times political columnist James Reston would muse in the early 1970s that over the past decade the United States had witnessed "the longest and most divisive conflict since the War Between the States."

Contemporary history continues to influence historical memory. And although as the authors of Like a Civil War we have tried to avoid the political and generational partisanship in our interpretation of the 1960s, we realize how unlikely it is that any single history of the decade will satisfy every reader. Perhaps by the time centennial observances roll around for John Kennedy's inauguration, the Selma voting rights march, the Tet Offensive, and the 1968 Chicago Democratic convention, Americans will have achieved consensus in their interpretation of the causes, events and legacies of the 1960s. But at the start of the twenty-first century, there seems little likelihood of such agreement emerging anytime in the near future. For better than three decades, the United States has been in the midst an ongoing "culture war," fought over issues of political philosophy, race relations, gender roles, and personal morality left unresolved since the end of the 1960s.

We make no claim to offering a "total interpretation" of the 1960s in Like a Civil War. We do, however, wish to suggest some larger interpretive guidelines for understanding the decade. We believe the 1960s are best understood not as an aberration, but as an integral part of American history. It was a time of intense conflict and millennial expectations, similar in many respects to the one Americans endured a century earlier -- with results as mixed, ambiguous, and frustrating as those produced by the Civil War. Liberalism was not as powerful in the 1960s as is often assumed; nor, equally, was conservatism as much on the defensive. The insurgent political and social movements of the decade -- including civil rights and black power, the New Left, environmentalism and feminism -- drew upon even as they sought to transform values and beliefs deeply rooted in American political culture. The youthful adherents of the counterculture shared more in common with the loyalists of the dominant culture than either would have acknowledged at the time. And the most profound and lasting effects of the 1960s are to be found in the realm of "the personal" rather than "the political."

Living through a period of intense historical change has its costs, as the distinguished essayist, poet, and novelist Robert Penn Warren argued in 1961. Until the 1860s, Penn Warren argued, Americans "had no history in the deepest and most inward sense." The "dream of freedom incarnated in a more perfect union" bequeathed to Americans by the Founding Fathers had yet to be "submitted to the test of history": There was little awareness of the cost of having a history. The anguished scrutiny of the meaning of the vision in experience had not become a national reality. It became a reality, and we became a nation, only with the Civil War.

In the 1960s, Americans were plunged back into "anguished scrutiny" of the meaning of their most fundamental beliefs and institutions in a renewed test of history. They reacted with varying degrees of wisdom and folly, optimism and despair, selflessness and pettiness -- all those things that taken together make us, in any decade, but particularly so in times of civil warfare, sadly (and occasionally grandly) human. It is our hope that, above all else, readers will take from this book some sense of how the 1960s, like the 1860s, served for Americans as the "dramatization of our humanity."

Question about the book? Email me at misserma@hamilton.edu Return to book page:

![]()

![]()