Parallel to the development of music theory has been the appearance of music notation. Like music theory, the notation of music has been preoccupied primarily with the pitches and rhythms of music.

Forms of music notation have been identified in the archaeological remains of ancient Mesopotamian, Chinese, Greek, and other civilizations. The purposes of musical notation have been not all that different from those of other forms of writing:

Musical notation in the music of so-called "western" civilization first appeared by the 9th century in the form of little mnemonic markings, called neumes, above the text of the chant that was sung in church by the clergy (see example 1).

By the 10th century these markings had become increasing ornate (see example 2). As these markings became even more complex, it became necessary to add a horizontal line through them to provide a pitch reference. Soon it became necessary to add yet another horizontal line (see example 3) and then two more after that (see example 4). By the 15th century the staff of five lines had become established as a common notational practice (see example 5). (Since this time, there have been approximately 22 more generations of people, so the five-line staff became established in the time of your great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great grandparents).

The musical staff can be thought of as something of a time domain graph: the passage of time is marked horizontally, from left to right across the page, and pitch (the musical equivalent of frequency) is marked vertically.

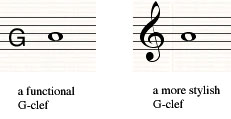

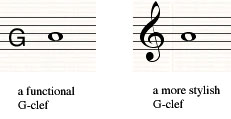

A stylized letter "C," "G," or "F" is placed at the beginning of the staff on one of the lines to establish a point of reference. The locations on the staff of the other notes in the scale can be determined thereby. This symbol is called a clef.